While searching for examples of lowrider (Roman-type) workbenches for Chris, I started to find images of workbenches from the Spanish Colonial era in Mexico and South America. As this is a field that is underrepresented, Chris and I thought it would be a good idea to assemble them for study. I found woodworking images from seven countries, with the majority from the early 17th through late 18th centuries.

Except for a very few, the majority of Spanish Colonial images are of religious scenes. In Europe, the shift from religious to secular images occurred earlier, but in the Spanish-controlled lands religious orders of the Catholic Church set up craft guilds for the converted indigenous peoples, and controlled much of the production of painting and other arts until the 19th century.

Paintings from Spain were used to communicate religious ideas and also served initially as examples to copy. And many copies were needed as churches were erected in every settlement, and new arrivals from Spain built new homes. In a twist that did not occur in North American, the Amerindians in Spanish-controlled territories began to infuse elements of their ancient cultures into the art they produced.

Along with workbenches, you will also see the basic tool kit in use, some sawing, angels and a few cats.

Mexico

In the image at the top (lightened to see detail) Joseph is using an adze at a simple staked bench. Note the cabinet in the upper left corner with the basket of tools and two planes. You will not see all of Joseph’s workshops so neat and organized. And there is a parrot.

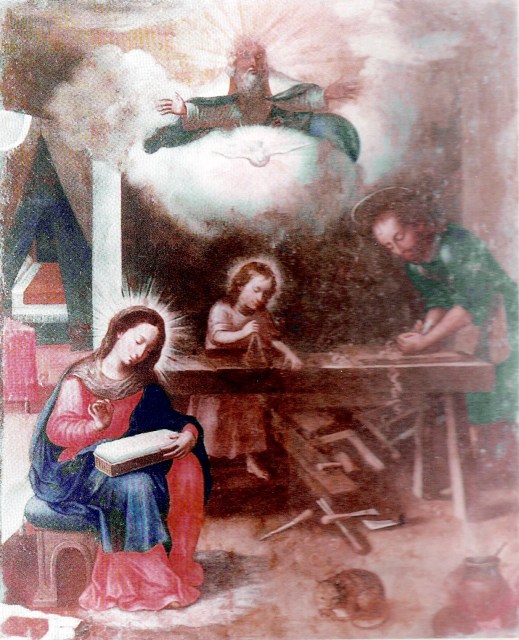

The painting above shows a simple bench with a substantial top and stretchers. A wall cabinet with a door is somewhat unusual in colonial paintings. Jesus has contrived a support for sawing on his own, no angels needed. This painting is probably a close copy of a European painting.

The painting above is from Oaxaca. Joseph and Jesus use a low and very long bench to support their sawing. There is a tool rack on the back wall and strewn about the floor are a selection of planes, chisels, an adze, square and mallet. It looks like Joseph is using his leg and a short bench as an additional support for the piece they are sawing.

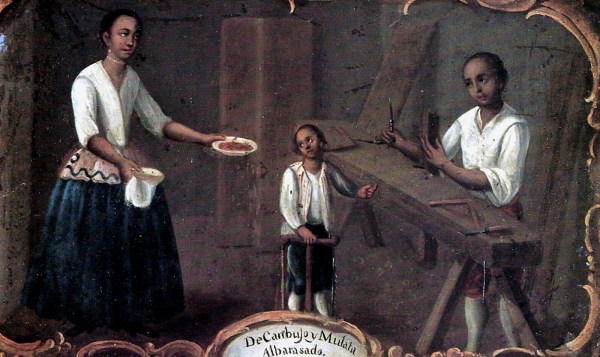

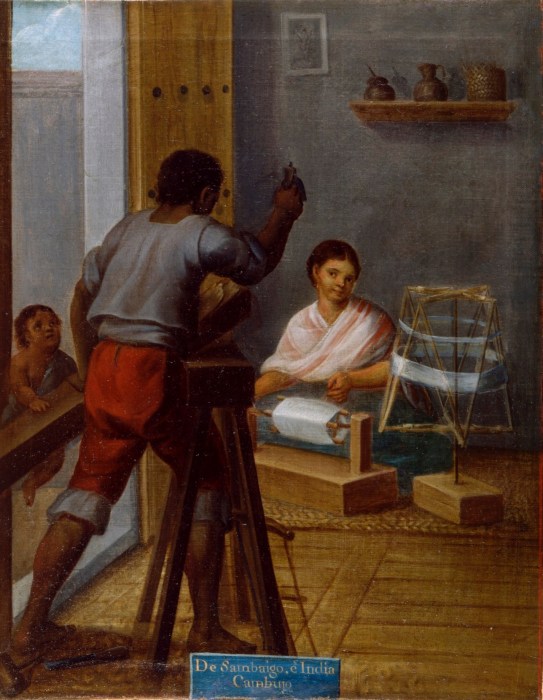

In Mexico in the 18th century a type of secular paintings were made to illustrate a complicated and legal caste system. Very briefly: with a population of Iberian Spanish, colonial-born Spanish, Amerindians and Africans there were bound to be intermingling; racial mixtures were used to determined levels of status. Casta (caste) paintings generally illustrated 16 mixtures.

In the secular trinity above we have a nice example of the staked bench, although a bit higher than Chris would like, and a small selection of tools.

Of the hundreds of Casta painting I looked at most of the craftsmen were shoemakers, so I was surprised to find some carpenters. With adze in hand he works the wood supported by his bench and child.

It is highly likely some of the workbenches are exact copies of benches in European paintings. As more immigrants and members of religious orders arrived, more paintings and other artwork was available to copy. However, I think the Casta paintings and paintings from missions point to the type of bench most commonly built and used in mission shops and by craftsmen working in city shops.

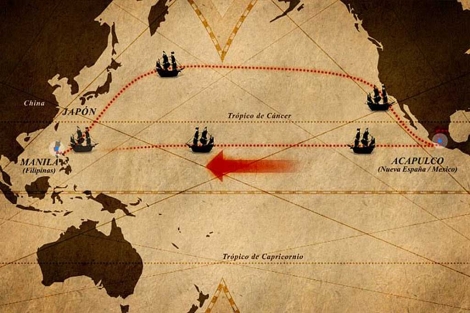

The Spanish-controlled lands in the new world became part of a global trade network that extended from Spain to Asia. Via “La Nao de la China,” otherwise known as the Manilla Galleon, precious metals found in the New World, especially silver, were transported to Manila to trade with Chinese merchants.

The Manilla Galleons ran from 1565-1815 and ultimately completed two voyages a year using the largest ships in the world. The goods from Asia landed in Acapulco with some distribution in the New World. The bulk was moved over land to the Atlantic Ocean and thence to Spain. The human cargo consisted of slaves and freeman and with them the colonies were exposed to new materials, methods and influences.

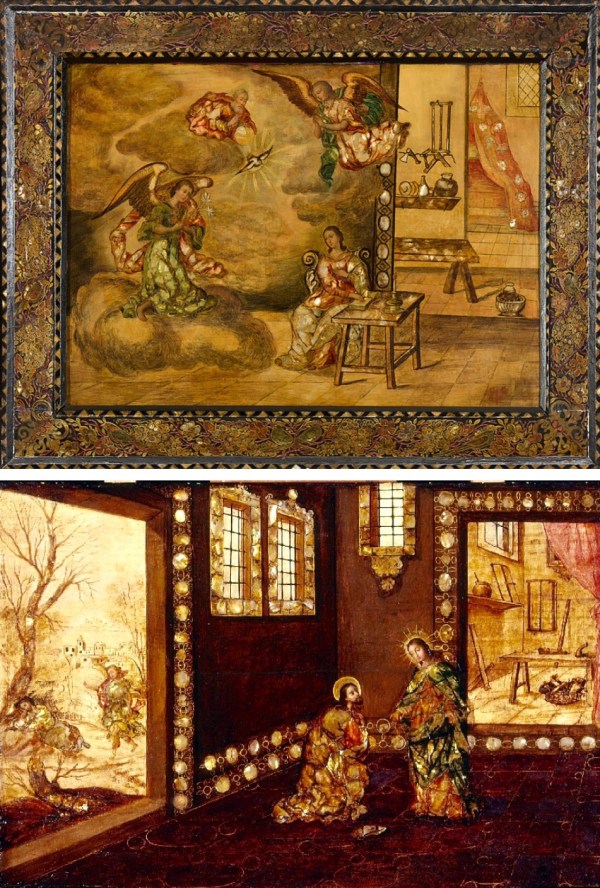

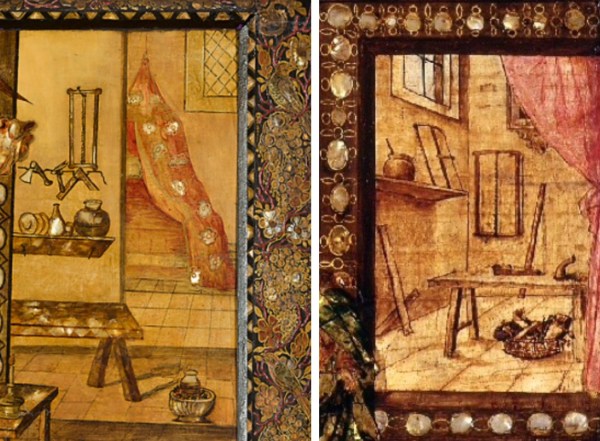

One example is the use of mother of pearl for inlay (a craft the Japanese had perfected) which became known as enconchada. In paintings it was generously used to impart a richness to the subject. In dim churches and homes, the garments of Mary and Joseph, angel’s wings and the embellishments around doors and windows would glimmer and glow.

Back to the benches. Similar low staked benches, one with stretchers. On the left there is the not-recommended tool storage above the dishes. On the right, we have a sensible woodworker with only a gluepot (?) and a smaller saw on the shelf and a nice basket o’tools.

In the Mexico gallery there is a painting with bench that may be a reproduction, more glowing, some polychrome sawing and a vista. Click on each image for a description.

To wrap up Mexico here is a 19th century bench of a master carpenter.

The legs look like they have been replaced. The bench is 228 cm long and 127 cm wide. Chris commented that he suspects the face vise screws are so long to accommodate sawing pieces for veneering. My contribution is to name the nuts “double-bunny ears.”

Colombia

Flemish paintings brought to the colonies introduced the idea of spiritual scenes warmed with details of domestic life. This is very likely a close copy of a European painting.

Jesus is a bit older and has his own bench. Both benchtops seem to have holes for pegs (or a holdfast) to use for work holding.

The right leg on Joseph’s bench seems to have holes and perhaps a holdfast.

This painting is from Medellin. The staked bench has a substantial top and legs. Tool collection on the ground and a cat.

Nice heavy bench top and a face vise with indeterminate nuts.

Staked bench with a very skimpy top and wonky legs, but you get the idea. The same set of tools strewn about. Baby Jesus is not using a safe chiseling method.

I add subtitles to images in my notes to remember which is which. This one is, “Get that baby off that bench!” But, we are back to the long and narrow staked bench. Demerits for the Baby Jesus on the bench (with chisel), merits for using a basket for tool storage.

Chisels in a rack on the wall, squares, planes, mallet, and saw on the floor. Dividers and adze on the bench. Bench more than a bit too high for its legs. Wait! What is that NOTCH on the front edge of the benchtop? I can’t repeat the exclamatory phrase Chris used when I sent this image to him. I believe this bench joins the Roman Saalburg workbenches in Workbench Mystery No. 326 (read that post here).

The Colombia gallery has two more benches and a vista.

Ecuador

Isabel de Santiago was the daughter of a well-known painter. Using her will, and other documentation, it was determined she had painted several paintings attributed to her father. Of course, the re-attribution occurred a few centuries after she died.

Joseph is about to strike a chisel with his mallet. An angel with dividers in one hand and a square in the other works alongside Joseph. The bench is similar to others earlier in the post with the addition of a cat and dog.

I had almost given up on finding a clear and uncropped image of this painting.* The bench has a face vise with hurricane nuts. There is a tool rack on the wall and minimal tossing of tools to the ground. The painter, Miguel de Samaniego, a mestizo, is considered one of the premier painters in Ecuador’s colonial era. He clearly had a sense of humor.

He gave Joseph a plethora of shop angels: naked angels are ripping, but who is supporting the other end of the wood? Joseph’s leg? The clean-up crew is busy. The chickens are being fed. Over at the soup pot, one angel blows air to stoke the fire while another suffers from smoke inhalation. And under the bench we have a spoon carver.

A staked bench with no face vise. Just as Joseph is about to bring his adze down, his helper angel puts finger to lips in the international sign of “Shhh” and points to the sleeping Jesus.

In the Ecuador gallery there is another painting by Isabel de Santiago (Joseph and bench are in the background), from the coastal city of Guayaquil a painting of Joseph with his tools and two vistas.

*A big thank you to Jaime H. Borja Gomez and his ARCA project. I was able to find missing information and better photos of previously found paintings, and many more images I would not have otherwise found.

I hope to have the next post up in a few days and it will cover Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay and Argentina.

— Suzanne Ellison