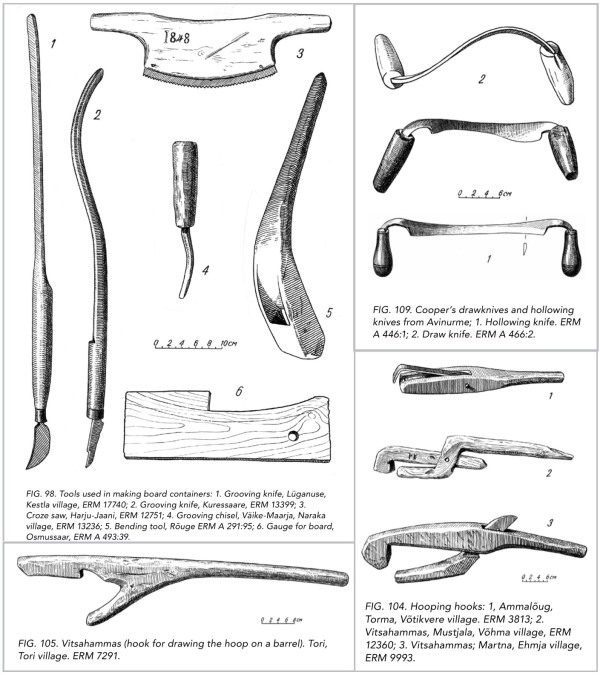

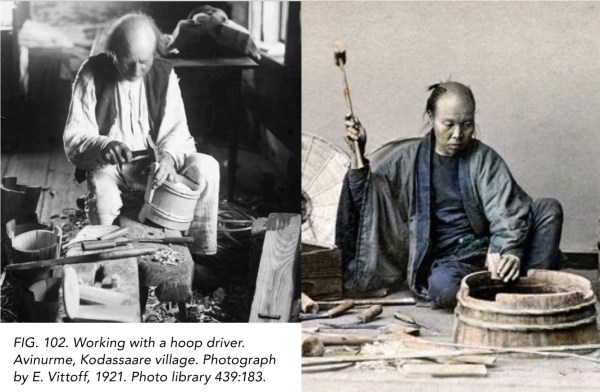

You never know what you might find when viewing Fujisan in a Japanese woodblock print. The tool the cooper is using looked very familiar and then I remembered the tools from “Woodworking in Estonia” by Ants Viires. The bigger Japanese tool may be a spear plane but in Estonia it was a grooving knife.

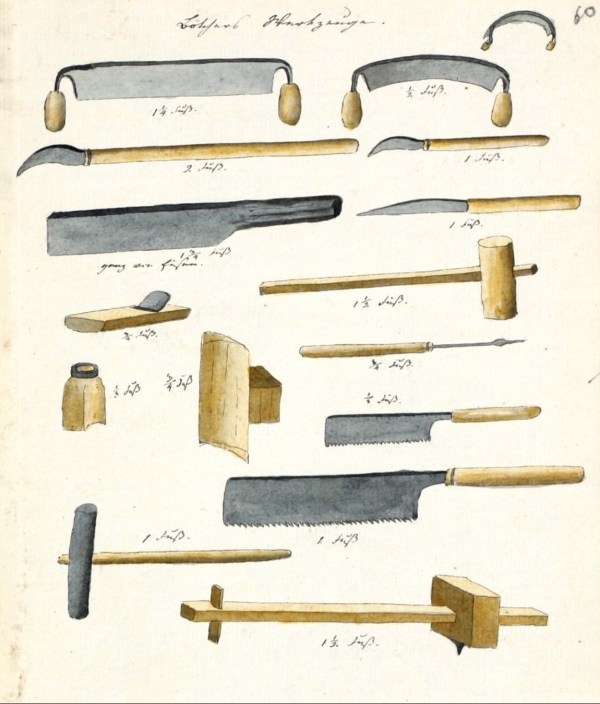

The Estonian tools in use at the time of Ant Viires research in the first half of the 20th century were likely no different from the tools used a century or more earlier. Besides the the size difference in the spear plane and grooving knife I wondered how the Japanese cooper’s tools might compare to those of the Estonian cooper. A quick search turned up the plate below and oddly enough it was in the National Archives of Estonia.

The handwritten title in German translates to “Cooper’s Tools.” No date was provided for this plate but the notations beneath each tool give a clue. The notations provide a scale in the old German measurement, the Fuß* (fuss, or foot). The Fuß was in use until the beginning of 1872 when use of the metric system became compulsory. To find out how long was the Fuß (good luck!) see the bottom of the post for some conversions.

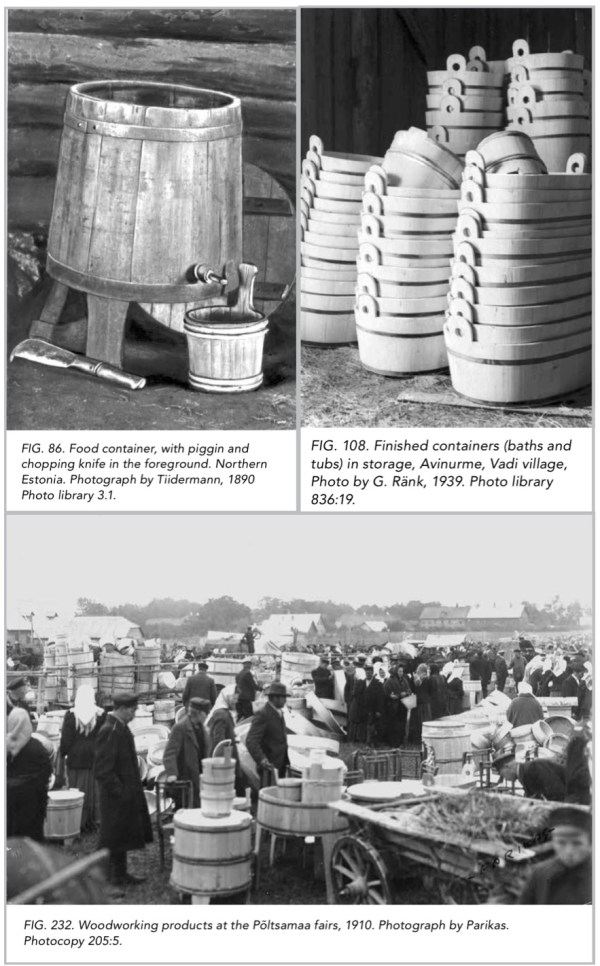

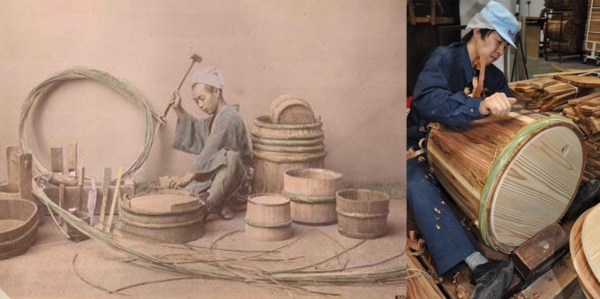

Looking beyond the tools the next question was what were the Japanese and Estonian coopers making and were there any similarities. Going back to “Woodworking in Estonia” I pulled a few photos that date from 1890 to 1939.

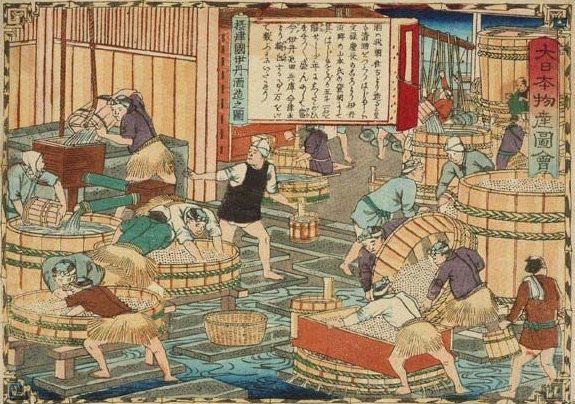

As described by Ants Viires coopers made buckets, churns, wash tubs, small baths, beer casks and containers for grain and other food storage. For merchants there were larger barrels for beer, food and many other commodities. For the Japanese cooper it was much the same with the addition of very large barrels for production of fermenting sake and soy sauce.

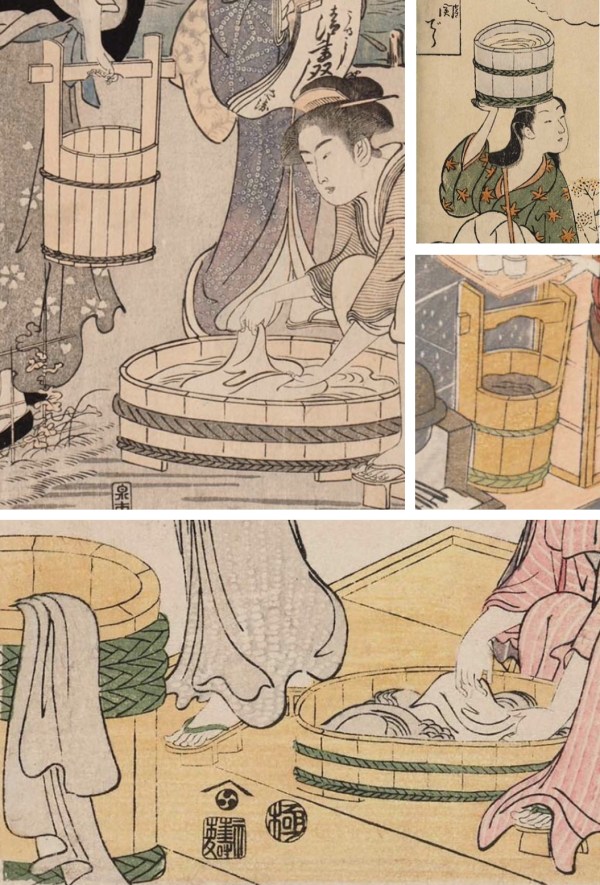

Many woodblock prints feature domestic scenes with women using buckets and tubs for bathing, washing clothes and for food preparation (I left out the bathing scenes). Much larger tubs and barrels can be seen in making sake.

One of the differences between Japanese and Estonian cooperage is the material used for the hoops. Estonian coopers used small branches, and later, iron for hoops. The Japanese used braided bamboo, then iron and copper. Traditional craftsmen making small pieces and companies using huge barrels for making soy sauce still use braided bamboo for hoops. Overall, there are more similaries than differences in the methods, tools and items made by the Japanese and Estonian coopers.

With so many similarities the next question is about the roots of cooperage in each country. Open wood buckets made using the methods of a cooper have been dated in Egypt to 2690 BC and fully closed Iron Age barrels have been found in Europe from 800-900 BC. By the 1st century BC barrels were in wide use for beer, wine, oil and water. Celtic tribes in Europe can be credited with making and using barrels for beer and wine. Next, here come the Romans because they always seem to be part of adapting, refining, inventing or spreading new technologies.

The Romans, like the Greeks and many early Mediterranean civilizations, used clay containers for storing and transporting wine and oil. Roman rule over the Celtic tribes of Gaul began in the 2nd and 1st c. BC and continued until 486 AD, and it was in Gaul they encountered the barrel. They found wooden barrels a vast improvement over clay amphorae for transporting wine and the added benefit of an improved taste to their wine, especially when the barrels were made of oak.

Did the early Estonian peoples learn cooperage from the Romans? Although Roman coins have been found in Estonian we don’t know if there was a direct connection.

Baltic tribes had trade contact with the Romans via the Amber Road. The Amber Road (actually a network of routes) extended from the North Sea and Baltic Sea to the Mediterranean.

Highly prized, amber from the Baltic has been found in Egypt from 16th c. BC. Like the East-West Silk Road, the Amber Road was a conduit for trading commodities and technology.

For five centuries the Romans controlled Gaul and that extended presence did exert an influence on Germanic tribes not under Roman control. If the Baltic tribes in the area of Estonia did not aquire knowledge of cooperage prior to the end of Roman control the technology may have arrived via trade or war contact with Germanic tribes, or during later invasions by others.

When did Japanese coopers learn their craft? In yesterday’s news (what timing) there was a report that Roman coins had been found in the ruins of a 12th century castle in Okinawa. What next, Vikings? The archeologist overseeing the site said there was no evidence of Western contact with the ancient Okinawan kingdom, but the Chinese did have extensive trade contact with the West from the 14th through the 19th centuries. The coins were probably traded between the Chinese and the Okinawans.

For millenia Japan had extensive trade and cultural contact with its neighbors, in particular China and Korea. During the Nara period (710-794) Japan turned more inward and concentrated on cultivating its native crafts, especially woodworking, ceramics and textiles. As for cooperage, we known that sake has a history extending back 1700 years. In the 8th century sake was favored by, and became regulated by, the Imperial Court. The Imperial regulations covered all portions of the production of sake and included the barrels used.

Soy sauce production dates back about 1500 years and one of the key ingredients of the fermenting process is using kioke, barrels made of cedar. After World War II soy sauce companies were urged to use stainless steel vats instead of the cedar kioke.

On the island of Shodoshima the soy sauce makers did not agree and continued to use kioke. In 2012 Yamamoto Yasuo the owner of Yamaroku Shoyu traveled with two carpenters from his company to learn the traditional method of making kioke from preparing the cedar slats, making the bamboo pins and selecting and braiding the bamboo hoops. They worked with Ueshiba Takeshi of Fujii Wood Work in Osaka Prefecture. They now make there own kioke and other producers are following their lead to revive and continue the traditional craft of making the huge barrels. A short (7 minute) video on making a kioke and the braided bamboo hoop is here (it is really cool).

One of the themes Ants Viires highlighted in “Woodworking in Estonia” was the decline of traditional crafts and the use of plastic items to replace wood. This lament is also heard in Japan and more efforts are underway to work with elderly craftsmen to learn and document traditional craft. In Kyoto this movement is particularly strong.

Nakagawa Shuji, an oke maker (oke are the wooden tubs) in Kyoto was interviewed by Kyoto Journal. Nakagawa talks about his apprenticeship and efforts to keep his traditional craft alive. The oke he makes are refined and copper is used for hoops. In the middle photo below he holds the sen, the two handled plane, that dates back to medieval times (1185-1600 in Japan). You can read the interview with him here.

Conclusions: although the Romans seemed to have left their coins everywhere they did not originate nor spread cooperage around the world. Good ideas and sucessful technology don’t have to have a single point of origin. With some variations in tools and techniques, when humans need to make something to improve their lives they often travel the same path.

–Suzanne Ellison

*There was no standardized measurement for the old German Fuß as it changed through time and it also depended on where you were living in Germany, Austria, Switzerland and parts of France. Here are conversions as recorded in 1830 in three places (chosen to show the range of the Fuß measuremnt and because I either lived or visited these cities as a child): Mainz – 314 mm or 12.36 in, Metz – 406 mm or 15.98 in, Würzburg – 294 mm or 11.57 in.