This is an excerpt from “The Joiner and Cabinet Maker” by Anon, Christopher Schwarz and and Joel Moskowitz.

For those of you who chisel out your waste when dovetailing, this section is not for you. Move along. There’s nothing to see here.

OK, now that we’re alone: Have you ever been confused about which frame saw you should use to remove the waste between your pins and tails? I have. For years I used a coping saw and was blissfully happy.

Then I took an advanced dovetail class with maestro Rob Cosman and he made a strong case that a fret saw was superior because you could remove the waste in one fell swoop (instead of two). So, like any good monkey, I bought a fret saw and did it that way for many years.

But fret saws aren’t perfect. Almost all of them require tuning. You need to file some serrations in the pads that clamp the blade, otherwise it’s all stroke, stroke, sproing. Oh, and the blades tend to break. Or kink.

And fret saws are slow. I use 11.5 teeth per inch (tpi) scrollsaw blades, and it takes about 30 strokes to get through the waste between my typical tails in hardwood.

If you want to see a good video on how to tune up a fretsaw, check out Rob Cosman’s site. He shows you how to hot-rod the handle and bend the blade for the best performance.

About Coping Saws

What I like about coping saws is that they cut faster. I use an 18 tpi blade from Tools for Working Wood. (I think they’re made by Olson.) The blades cut wicked fast thanks to their deeper gullets and longer length. It takes me 12 to 14 strokes to remove the waste between my typical tails.

The other thing I like about the coping saw is that its throat is deeper (5″ vs. 2-3/4″ on my fret saw), which allows me to handle wider drawers without turning the blade. Also, the blades of a coping saw are far more robust and almost never come loose. I’m partial to the German-made Olson coping saw. It’s about $12 and beats the pants off the stuff at the home centers.

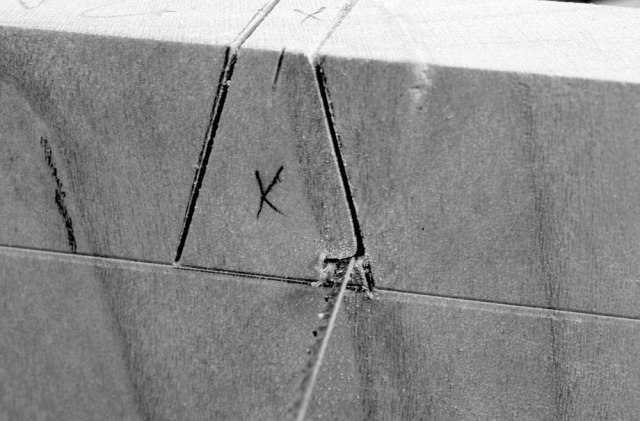

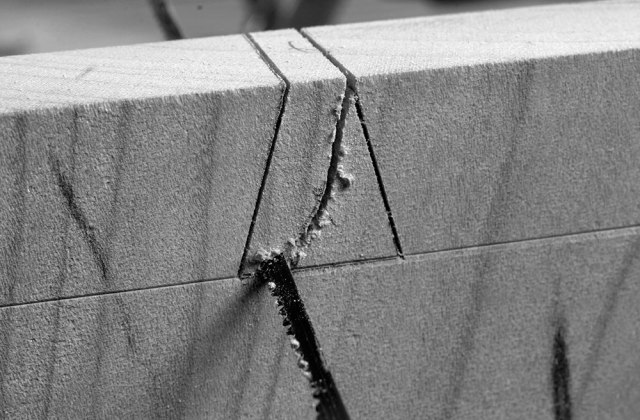

The major downside to the coping saw is that you have to remove the waste in two passes instead of one. Because the coping saw’s blade is thick, it sometimes won’t drop down into the bottom of the kerf left by your dovetail saw. So you get around this by making two swooping passes to clear the waste.

One last thing: Some of you might be wondering why I didn’t discuss wooden bowsaws, another fantastic frame saw. At the time I was writing this book, my bowsaw was busted. First, one of the arms cracked after someone (no names) over-tensioned it. I fixed that. Then the twine busted and I didn’t have any on hand.

Since building the Chest of Drawers, I got my bowsaw back on its feet (bowsaws do not have feet, by the way) and it is giving my coping saw a run for its money. The fret saw still hangs dusty and lonely on the wall.

— MB