Let’s say, for example, that you really like the taste of armadillo meat.

You love it poached, pan-fried and in a white wine sauce. Your taste buds can tell when one had nibbled on some acorns.

But let’s also say that at the zoo, you can’t distinguish a live armadillo from a peacock.

I know, that seems crazy. But when it comes to trees, most woodworkers can’t tell the difference between red oak and white, an ash from a birch, and on and on. Most woodworkers – no lie – are lucky if they can distinguish between a tree and an ornamental tree-bush thing.

Is this important? I think so.

Trees have always been this continent’s greatest natural resource. And our close relationship with trees separate us from almost every other culture on the planet. The North American civilization was built on trees. They are the backbone of our homes. Their abundance is the reason that woodworking is so popular here. They are still one of our biggest exports and one of our greatest resources.

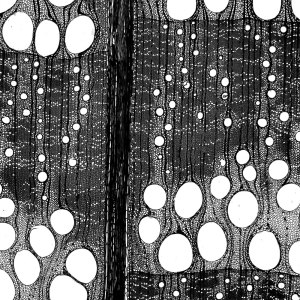

And that is why my kids can tell the difference between a maple and an oak and a freaky osage orange (the brain tree). If you know a little about the black cherry, the sugar pine or the hardy catalpa, then working with that species is more gratifying and awe-inspiring. You’ll know when you have a piece of wood on your bench that grew quickly, or struggled in rocky soil. You’ll be able to identify when some unscrupulous lumber merchant has sold you reaction wood from the branches of a tree. You’ll see knots and other structures in a whole new light – not as a defect necessarily, but as part of the tree that you can work with or work around.

This week, we have put the finishing touches on Christian Becksvoort’s first book with Lost Art Press titled “With the Grain: A Craftsman’s Guide to Understanding Wood.” This book is the foundation for a long relationship with our raw material.

To be sure, this book is 100-percent practical. There’s no swooning over grain patterns in its 144 pages. Instead, it is an examination of the material from a furniture-maker’s perspective. And Becksvoort has three important lessons:

1. Know the trees around you and know that they can be used to build furniture.

2. Understand how wood moves and how to use the simple formulas and charts that can tell you exactly how the stock on your bench will change with the seasons.

3. How to build your projects so they allow the wood to move without splitting the wood or destroying your joinery.

All this is told in a concise, clear and direct manner – illustrated with hundreds of photos and line drawings. If you have ever wondered about the relationship between the trees in your neighborhood and the wood you use to build furniture, I think you will appreciate this book and the way it links everything together.

“With the Grain” is available for $25 with free domestic shipping (until Feb. 20) from our store.

— Christopher Schwarz