I’ve built more workbenches than any other woodworking project. I’ve taught more workbench classes than any other type of class. And I’ve written more words about workbenches than I care to remember.

During the last two decades, I’ve encountered six distinct personalities of workbench builders. These are the six little angels (or devils) that sit on my shoulders as I peck away at my laptop on my latest effort: “Ingenious Mechanicks: Early Workbenches & Workholding.”

I’d like to introduce you to them. I am quite fond of all six. But all six drive me a bit bonkers at times. Let’s start with “The Engineer.”

Workbench Personality No. 1: The Engineer

It begins with a discussion of the wood selection for the top. The engineer looks over the stock and begins measuring the angles of the annular rings on the end grain.

“This top,” he says, “will never remain flat.”

He’s done the calculations for how much each stick will move tangentially and radially. The conclusion: These pieces of wood cannot be joined into a benchtop that will move homogeneously throughout the yearly humidity changes. He wants all his sticks to be perfectly quartersawn. Or, at the least, all the annular rings should be at nearly the same angle to the true faces of each board.

I attempt to explain how flat a top needs to be for typical planing operations (not very flat), and that it has to be reasonably flat in only certain areas of the benchtop (near the front 12” of the benchtop). I take away his feeler gauges when he isn’t looking.

When cutting the joinery for the base, I implore (beg, really) for all the students to make their tenons fit loosely. The tenons should fall into the mortises – like throwing a hotdog down a hallway. This makes the bench much easier to assemble and faster to build. Drawboring will lock the joints together instead of glue.

The engineer asks: Won’t a loose fit make the joints weaker? And therefore the overall bench?

Me: Not in any meaningful way.

Engineer: Prove it.

He makes his tenons so they are .002” smaller than the mortise opening. (“That is loose” he protests.) When he’s in the bathroom I take a wide chisel and pare slightly the walls of his mortises. When glue-up time comes, he’s amazed that the bench goes together so easily.

Me: The glue is acting like a lubricant.

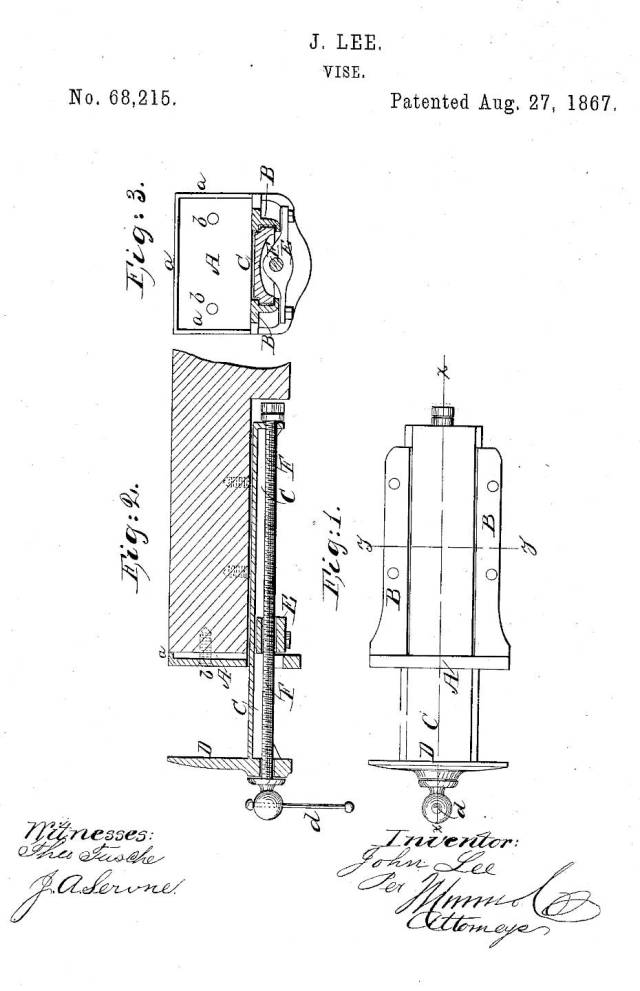

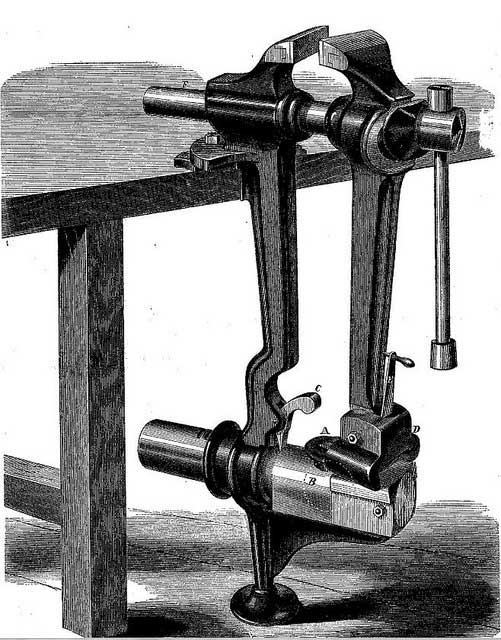

We’re installing the vises. The engineer isn’t satisfied with the bushings and bearings used on the guide bars. He recommends we overnight some alternative raw materials from MSC that we could mill up the next evening. Also, he has drawn up some sketches of shielding we could construct that would prevent dust from ever landing on the screw mechanism. Perhaps they could run in a sealed oil bath.

After the class adjourns for the day I drive to my hotel to drink a beer and sleep – thrilled that a throng of engineers built my vehicle and made it safe. But I’m also hoping against hope that that The Engineer will discover LSD, marijuana and Ecstasy that evening and is going to show up to class the next day in a Hawaiian shirt and flip flops.

— Christopher Schwarz, editor, Lost Art Press

Personal site: christophermschwarz.com

Next up: Workbench Personality No. 2: The Traditionalist