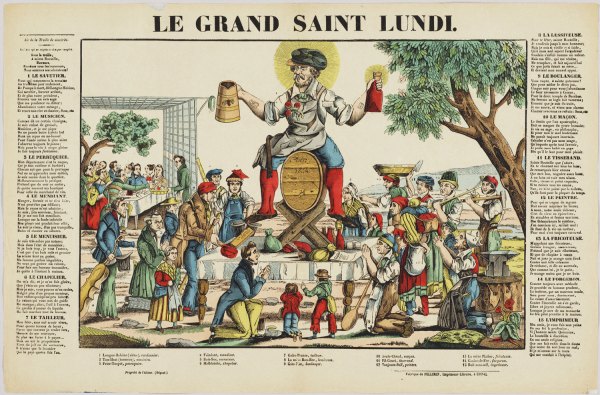

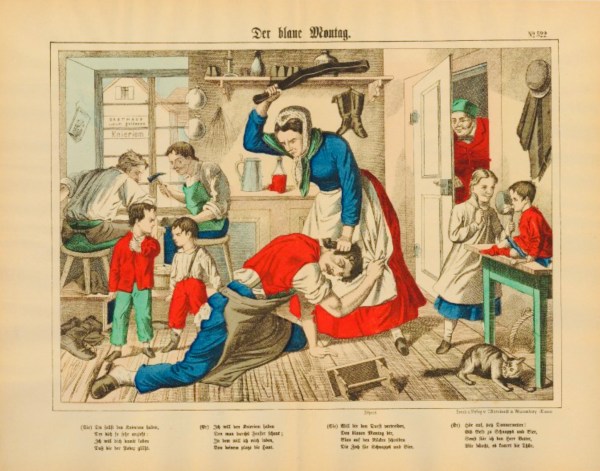

Bacchus in the form of Saint Lundi sits astride a barrel and offers drinks to a group of craftsmen. Each craftsman has his own verse in the song printed on the broadsheet. Spot the menuisier and read his verse to the left of the image.

“I drink to the general joy of the whole table.”

After working at least a half-day on Saturday and then collecting their pay, workmen could look forward to Sunday and a full day off. In this account published in 1824 the writer differentiates between the married and the unmarried mechanic. Contemporary accounts tell us the married mechanic often joined his unmarried companions in Saturday night drinking.

From Ivan Sparkes’ article on the chairmakers of High Wycombe, England we have this description of Saturday activities after the week’s pay was received.

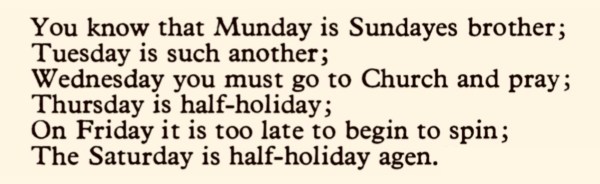

The revelries and drinking continued into Sunday and when Monday morning dawned there were many workmen not in much of a state to return to work – so they didn’t. For those observers of this tradition, Monday became known as Saint Monday in Great Britain, Ireland and America. This ditty is from England in the 17th century:

In 1546 there was an effort in the Venice Arsensal to stop the arsenalotti from observing Saint Monday. They were threatened with a loss of pay for the entire week. Although the workers would make up the lost day by working longer hours the rest of the week, the loss of work on Monday was too disruptive to the organization of a shipyard. Because of inconsistent enforcement of the pay penalty the observance of Saint Monday continued.

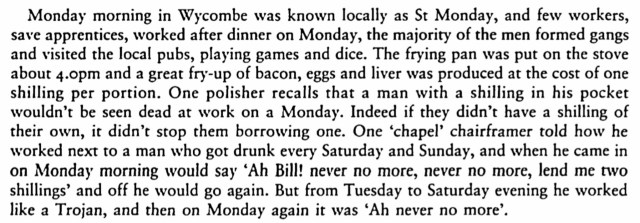

The chairmakers of High Wycombe provide another example of Saint Monday.

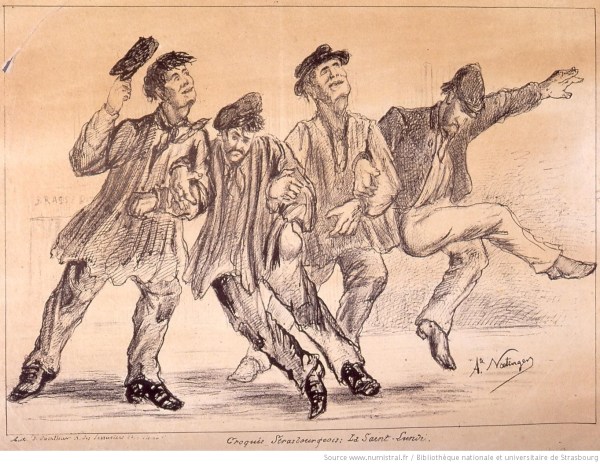

Much of the the images available for Saint Monday were generated in France. I leave it to you to surmise why that may be.

In France and Belgium Saint Monday was, of course, Saint Lundi. One 19-century French writer referred to Saint Lundi as an uncanonized saint. I can’t think of a better description.

When workmen took Monday as a second day of leisure they weren’t necessarily drinking the entire day. It was also a day for playing games (skittles were popular in England), taking a ramble through town (including a few stops at taverns) and time for trade union meetings.

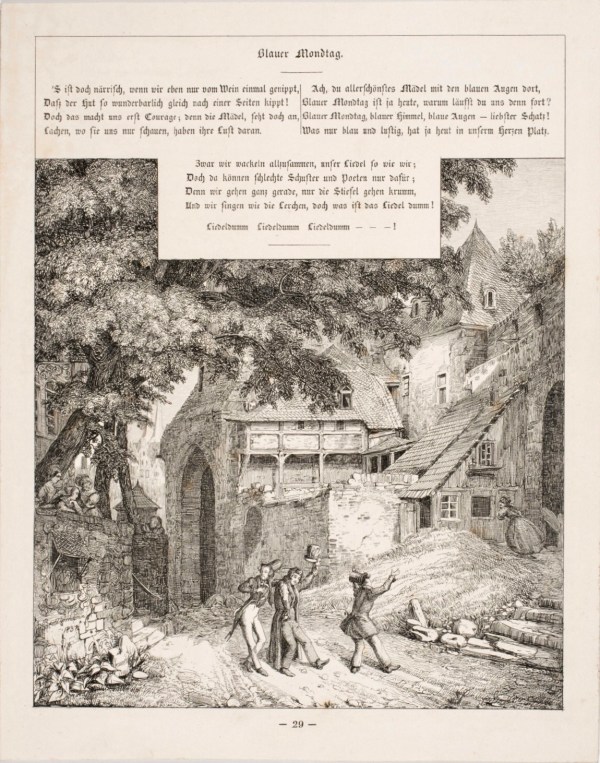

In Germany, Saint Monday was known as Blauer Montag (Blue Monday).

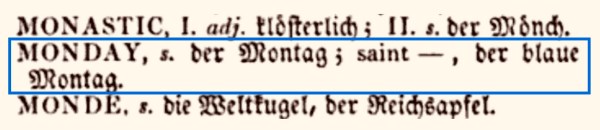

Blauer Montag was widespread enough to earn a place in Flügel’s 1857 German-English dictionary.

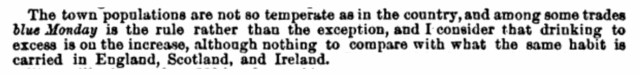

An American gathering information on wages and living expenses in Europe during the 1870s made this note about Germany:

Cordwainers (shoemakers) were often at the forefront, both in Europe and America, of the push for better working conditions and a shorter workday. They were also noted as some of the most fervent followers of Saint Monday and consequently are often seen being beaten by their wives.

The observance of Saint Monday began to fade away towards the end of the 19th century and prevalence of the factory system. However, Saint Monday was another step in the working class effort to gain more control over their work lives and to have more time for rest and leisure.

”Why, sir, for my part I say the gentleman had drunk himself out of his fives senses.”

Just how much alcohol was being consumed? In 1770 Americans averaged 3-1/2 gallons of pure alcohol per person per year. This is not gallons of a specific spirit, rather a total of all alcohol content. The apogee (or perhaps the nadir) of American consumption was in 1830 when the average consumption was 7.1 gallons of pure alcohol per person. Per the 1830 census the population was 12.9 million. One of the drivers of alcohol availability came from corn in the Midwest. Corn would spoil if shipped to the coastal states, however, it could be distilled and shipped as whisky instead. Whiskey was cheap and easy to buy.

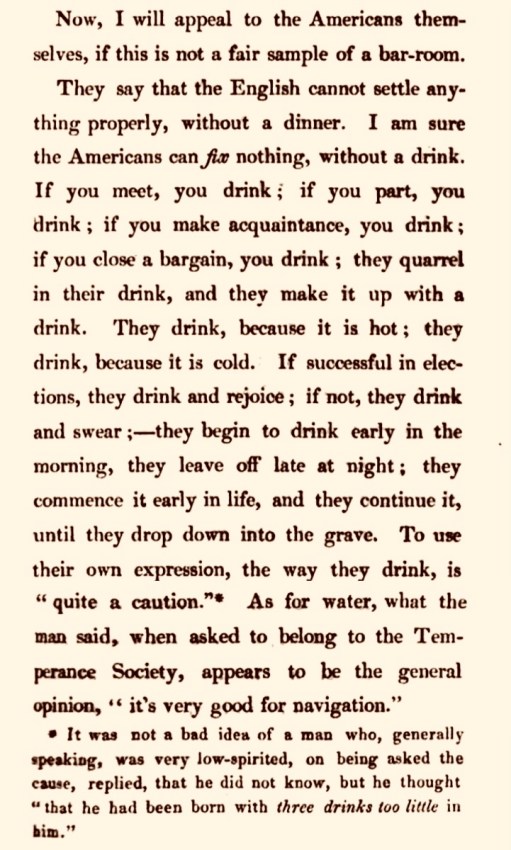

In 1839 a Captain Marryat from England visited America and wrote a multi-volume “Diary in America.” In the section titled “Travelling” he expressed these observations about the drinking habits of America:

In the state of Virginia he commented on the consumption of large quantities of mint juleps and noted “you may always know the grave of a Virginian; as from the quantity of juleps he has drunk, mint invariably springs up where he has been buried.”

He also enjoyed an American champagne.

Edward Young, an American gathering data on wages and the price of living in Europe in the 1870s, was flabbergasted that Belgium had “about one hundred-thousand licensed public houses…for the supply of five million inhabitants.” For every 48 inhabitants there was 1 liquor shop.

In Germany he contrasted the unmarried man with the married. The unmarried laborer rented a bed in a room with others in lodgings close to the workplace. Spending time in a tavern was essentially the only place to relax. Beer, bread and a little meat made up a large part of the diet of both married and unmarried men.

Surveying Great Britain, Edward Young commented “The fact is not forgotten that this investigation is made by a citizen of a country which, next to Great Britain, is perhaps most noted for its large consumption of intoxicating beverages – a country which expends over $600,000,000 annually in spirituous, vinous, and malt liquors.” Based on a report from 1872, England (not all of Great Britain) consumed more than 72 million gallons of pure alcohol at a cost of £120,000,000. At least half of this money was spent by the working classes.

I have just a few comments on the gin epidemic in England that began late in the 17th century and extended well into the 18th century. Gin was very cheap to make and buy and was sought by many as a relief to poverty. Men, women and children were addicted and it ravaged London. There was a “pandemonium of drunkenness” and ruin. A sign over one popular gin shop advertised “Drunk for a penny, dead drunk for two pence, clean straw for nothing.” William Hogarth’s 1751 etching titled “Gin Lane” is thought to capture the misery of the epidemic. You can easily find much more on your own.

The 18th century is also when temperance efforts gained traction and physicians began to think of alcohol addition as a disease.

“Ask God for temp’rance. That’s the appliance only which disease requires.”

In 1722, a century before America reached peak alcohol consumption, Ben Franklin was cautioning against drunkenness and overindulgence. By 1840 there were temperance societies to be found in every state with many affiliated with religious groups. In May of 1840 six Baltimore friends, all artisans, met and decided to stop drinking. Their approach was different from other groups as each member stood and talked about their lives as drunkards (the term alcoholic was not yet used). Their emphasis was on compassion and understanding for the addicted man. They named themselves the Washingtonians, after George Washington, and pledged to stop drinking all alcohol. The group grew rapidly, and as far as we know, it was the only temperance society founded by craftsmen.

The British Workman, published in London, was a monthly magazine advocating healthy living, Christian ideals and temperance. It was filled with illustrations, short stories and testimonials and was advertised as “dedicated to the industrial classes.” The masthead changed each month and featured sketches of men working at various jobs.

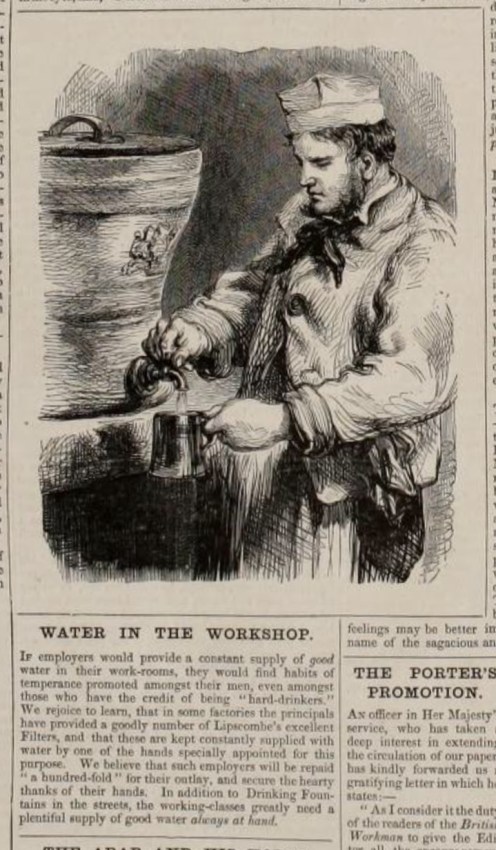

The magazine frequently urged employers to provide fresh water for workers in an effort to curb alcohol consumption in the workplace. One well-known illustration from British Workmen has been separated from its intended message.

The craftsman in his paper hat is filling his mug with water, not beer! Did the intended message get lost in nostalgia for the image?

The many satirical drawings of the grim reaper looming over a very drunk man were not promoting temperance, rather a comment on society. In that vein there is a second Drinker’s Dictionary printed in 1886 by Silas Farmer & Co. of Detroit.

The cover stamp pretty much sends the message of the dictionary. A link to the dictionary is at the end of this post.

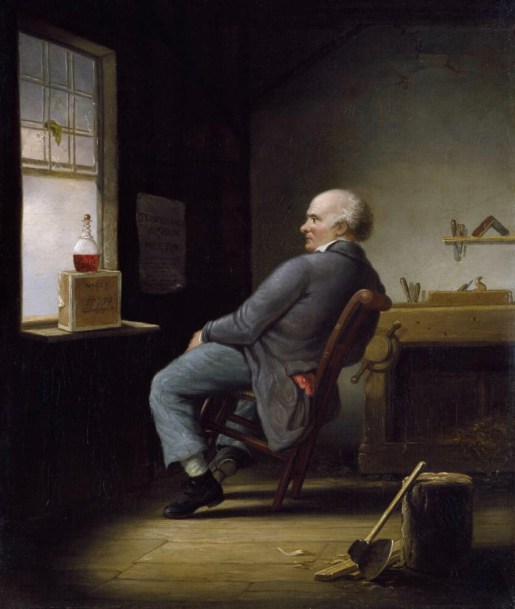

In 1845 Francis William Edmonds painted a carpenter sitting in his workshop.

The carpenter is “Facing the Enemy” and the scene captures the struggle of a man attempting to stop. He rocks back as though repelled but at the same time his eyes are locked on the bottle. Will he succumb?

In the darkness to the right of the open window is a broadsheet tacked to the wall. It is a notice for a temperance meeting. Side-by-side they are in a balancing act. The bottle offers ruin. The temperance meeting offers hope. That he still has a half-bottle of liquor tells us has not yet been able to let go. He took the trouble to put the temperance notice on the wall. His shop is neat and he has his jacket on. Is the temperance meeting that night and will he go?

Shakespeare and his Saturday-to-Monday Bender

After using quotes from the works of Will as titles for each section it is fitting to end with a tale from the 17th century. It seems to have some relation to the observance of Saint Monday.

The Drinker’s Dictionary of 1886 can be found here.

Our French readers can find more about Saint Lundi here.

The gallery has a bit more Blauer Montag, Saint Monday and Saint Lundi for you.

–Suzanne Ellison