In Part II includes more benches and angels, a new painting style, a mystery and a few other things. Get your snacks and drinks ready.

Peru

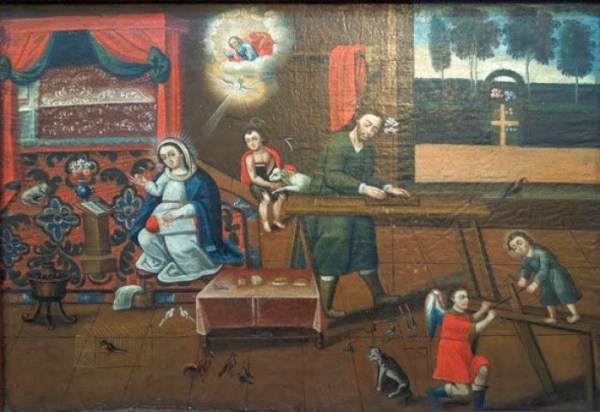

Peru starts in Cuzco, capital city of the Incas, and with the Quecha painter Diego Quisepe Tito. Tito is considered the most important painter of the Cuzco School, and his work includes at least four scenes of Saint Joseph engaged in woodworking. Although the painting above is dark with age we can see a simple bench without a vise. The background is too dark to see a tool rack, but there are a few tools on the ground.

When Joseph is in the background we usually can’t see much detail about his bench. In this painting it is easy to see there is a face vise with hurricane-shaped nuts on a staked bench. And Joseph is wearing a hat not usually seen on a member of the Holy Family.

A staked bench with a planing stop. Look a little closer and on the left side of the bench there is a board held upright by a face vise. A saw hangs on the wall, and I am happy to see a basket of tools.

Last night I tried to find a color photo of this painting and what I found instead was the sad news that the painting was one of 24 lost in a fire at Iglesia de San Sebastian last year.

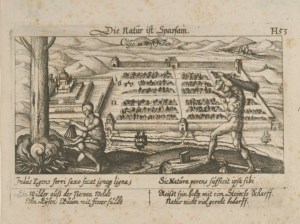

Both of these paintings are a copy of a Flemish engraving by the Wierix brothers. On the left, the artist was faithful to the original engraving keeping the toolbox (behind Joseph) and tools on the ground. The artist on the right changed the saw, perhaps copying a saw seen in use at the construction of a new building. He also left out the tool box and most of the tools on the ground. You might have noticed a whole new look to previous paintings. Brighter colors, intricate patterns (with matching birds on the left), gold leaf, native flowers and landscapes.

At the time the above paintings were done the Spanish had been colonizing the Americas for well over a century. A style of painting evolved in Cuzco when, in the late 17th century, Spanish-born and mestizo artists split away from the Amerindian artists of the painting guild. This freed the indigenous painters to incorporate colors and patterns from their cultures into copies of European art. It is thought Diego Quisepe Tito helped lead this effort that is now known as the Cusquena-style of painting.

A nice sturdy bench with stout legs. Only the axe is left on the ground. The chisels are nicely arranged in a basket with the divider used as a…divider! I think the artist may have given the bench such a great length in order to fill the lunette.

A staked bench with somewhat wonky legs, a parrot and Jesus at sawyer duty. Another trait of the Cusquena style you may have noticed is a lack of perspective.

If some, or many, of the colonial paintings seem familiar it is because of the use of a large set of engravings the Jesuits brought to the Americas to use in converting the indigenous peoples to Christianity. In the mid-16th century the founder of the Jesuits commissioned a series of engravings on the life of Christ from the Wierix brothers, well-known and prolific Flemish engravers. The commission was given in the mid-16th century by the founder of the Jesuits. The engravings were used in Jesuit conversions in their missions in the Americas and Asia.

The next three paintings are copies of Wierix engravings and show other woodworking scenes.

Joseph’s low staked bench sits at the bottom of a substantial gangway-type ladder.

Joseph, Jesus and the angels are building a lattice for the garden. The usual assortment of tools are tossed about.

Joseph is driving trennels into the boat.

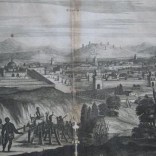

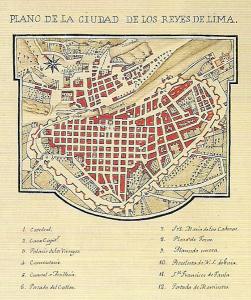

The gallery has one more Wierix-related painting, two vistas and a map.

Bolivia

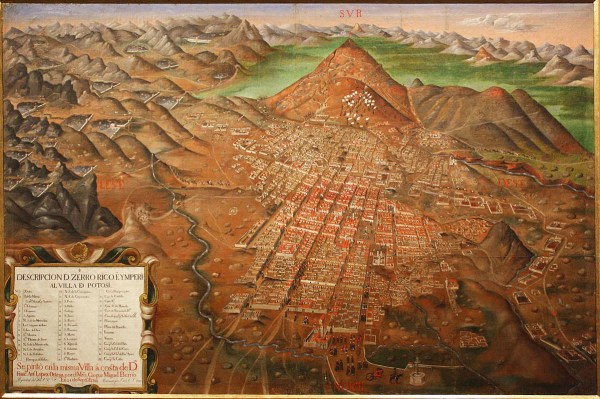

During the colonial era Bolivia was known as Alto Peru.

The silver mines of Potosi helped drive the trade with Asia and filled the coffers of Spain. During the height of its mining production Potosi was the wealthiest city in the Americas.

Melchor Perez de Holguin was a mestizo and the dominant painter in Potosi into the 1720s. Although the Cusquana style of painting was found in Alto Peru, de Holguin’s work falls into the Potosi school and was heavily influenced by the Spanish artist Zurbaran.

Joseph’s bench is much like those seen in other paintings from Peru and representative of all the benches I’ve found for Bolivia.

Although his workshop is in the background the painter did not stint on detail. The bench is staked with tapered legs. The plane is put aside while Joseph uses a chisel. His adze sits on the near end of the workbench. On the wall is a tool rack and on the floor another full set of tools.

I almost left out the next painting but something must have held me back.

It was the curvy legs (with stretchers!) and ornate plane. They were just too good to pass up.

This work is from La Paz. The bench is staked, has a planing stop and a face vise. There is a nice collection of tools even if they are all over the floor. OK, OK, if they were piled into a basket we wouldn’t be able to see them in such nice detail.

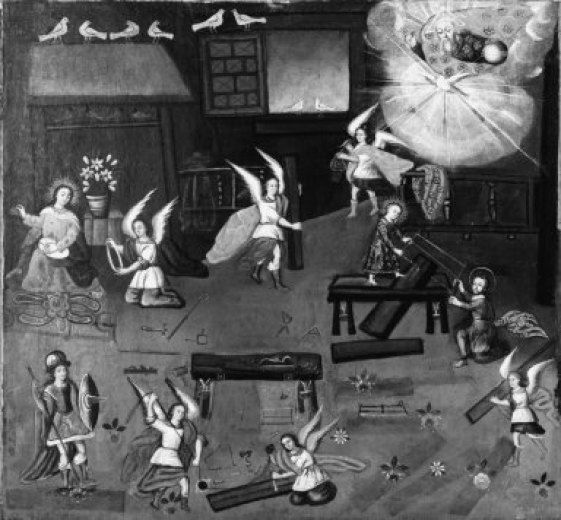

Because the painting is so dark the Brooklyn Museum provides a black and white copy to better see this frenetic workshop.

With non-winged personnel this may be a good representation of a colonial workshop cranking out furniture, doors and fittings for the non-stop construction of churches, private residences and governments buildings. There are two workbenches, both with face vises and a mystery.

Close-up shot of the bench in the middle of the painting. The white squares may be the vise screws (only this bench has these). But what are those mysterious things at each end of the vise? After much deep thought Chris surmised “rocks on strings.”

Despite the camera flash there is a staked bench with a face vise.

Isolating the bench shows, unlike others, the face vise does not extend the length of the bench.

This painting is spectacular in its detail: the wood grain on the board held by Joseph, Mary’s sewing cushion with thimbles in one pocket and thread in the other, the cat under the table playing with a spool of thread and the scissors in the basket at Mary’s feet. Joseph works on a staked bench and behind him tools are arranged neatly on a rack.

You may have seen this image on Chris’ other blog. When I sent the image to him a few weeks ago he got a little crazy over the “doe’s foot” planing stop. Readers of this blog will recognize the planing stop as, ahem, the palm or ban qi, which originated in China. You can read the origin story of the palm here. The blog about the modern version of palm or ban qi can be found here.

The palm can hold a wide flat board in place on the bench or a board held on edge, and both without leaving a mark. So how did a bench appliance of Chinese origin get to 17th-century Alto Peru? The same way Asian workers and goods arrived: the Manila Galleons which sailed between Acapulco and Manila from 1565 to 1815. The palm is just one example of the early arrival of Asian techniques in the Americas.

You might be wondering who is that woman in the doorway, the one who has drawn the attention of the Holy Family. She holds a basin containing the Arma Christ, symbols of the Passion of Christ. In a European painting the woman might be Saint Ann, the mother of Mary. In this painting I believe she is Mama Ocllo, a mother figure from Inca legend who gave women the knowledge of spinning thread and weaving textiles. This is another example of Amerindian painters integrating their culture into Christian religious works.

The illustration is from “El primer nueva cronica y buen gobierno,” a publication from 1615 in the collection of the Royal Danish Library.

Argentina

I found only one workbench-related painting from Argentina.

The painting is from Cordoba and titled ‘El Hogar de Nazaret’ from 1609 by Juan Bautista Daniel (1585-1662). The bench is staked with a try plane resting at the far end. Most of the tools hang in a rack or on the wall.

The painting has long been in a private collection and this seems to be the only photograph available. The odd thing about it is Daniel is identified as a Dane in a plaque at the center-right edge of the painting. It turns out he was from Norway and arrived in the territory now known as Argentina in 1606. He made his way to Cordoba where he was granted permission to live and work.

Paraguay

The last stop on this Latin American tour is at Santa Rosa, one of the Jesuit missions in Paraguay known as “reducciones de indios.” It is also my favorite of all the Latin American paintings.

The fresco is by an unknown artist and is in a corner of the Chapel of Our Lady of Loreto at the former Santa Rosa mission. The mission was founded in 1698 and populated by the indigenous Guarani people. When the Jesuits were forced out in 1767 the missions were deserted and most fell into ruin.

The fresco frames the Holy Family with two columns. Joseph is using a chisel and maul to make cuts on a panel for eight-point star inlays. The middle figure is Jesus sawing (ignore the splotch that looks like a wing), and on the end is Mary. In all the other paintings where we see Joseph with a chisel his action in generic. Is he chopping a mortise or carving? We don’t know. Here, we can see what Joseph is making.

The fresco is first of all an important document in the history of the Guarani. Second, it illustrates a craft that is an important element of colonial design.

Geometric designs were not new to the indigenous peoples of the Americas. Pre-conquest, geometric shapes were used in stonework, metal, textiles and pottery.

The stars, sun and moon were observed and recorded by many indigenous groups. Stars as a symbol, particularly eight-point stars, are found in many cultures. It is part of the Moorish influence in Spanish art and architecture, and in Christianity it is a symbol of redemption or baptism and is also a symbol of Jerusalem. For a sailor an eight-point star is a compass rose or wind rose.

On the left is part of a folio from the 8th century ‘Beato de Liebano’ and on the right Mary’s gown in a Cuzco School painting.

The eight-point star was used extensively as wood, mother of pearl and metal inlays in furniture during the colonial era. The examples above are from chests, armoires and tables made in various parts of the colonial territories. The black ceiling with red stars is the ceiling of the fresco chapel (in some grand European cathedrals the ceilings are painted blue with gold stars).

So, from a humble fresco in a small chapel that somehow survived for over 300 years we learn quite a lot.

To wrap-up this survey of workbenches I think the staked bench (high or low) with a planing stop and maybe a face vise is the type of bench that was most often used in the colonial era. The painters were not working in a vacuum and only copying scenes from European engravings and paintings. They observed carpenters that arrived from Spain and the benches they built and used, benches that could be adapted for different construction needs. Also, some of the first secular paintings, the Casta paintings from Mexico, were not copies of European paintings and show this type of staked bench.

A Quick Tour of Tool Storage

You have seen tools on the ground, on the floor, in racks and shelves on the wall and stowed in baskets. All of these methods, or non-storage in the case of floor/ground, can be seen in European paintings. How did the woodworkers in the colonial era store there tools? Spanish-born carpenters probably brought their tools in small chests or wrapped in bags. Using baskets would also be a familiar method of storage.

Making baskets was a well-known craft in the New World. In the wedding scene above from the Codex Mendoza, an Aztec document from 1535, there are woven mats and a basket.

This lidded basket is from the pre-Inca Chancay society and dated 12th to 14th century (British Museum). It holds yarns and tools used by a weaver.

If you had a small collection of tools and needed a tough but lightweight storage and carrying solution, a basket would certainly fit the bill.

There is one other solution and possible only with the help of the angels: the sky rack.

— Suzanne Ellison