Ostensibly he keeps the village inn. His name appears over the door in the orthodox black letters on a white ground as a licensed seller of beer and tobacco. It is a pleasant little inn, and in the garden behind there are some choice plants of the old-fashioned kind in which the landlord takes a good deal of pride; but the trade in beer and tobacco is not very brisk.

They keep a gramophone at the ‘Swan’ at the other end of the village, and its seductive tones seem to have an attraction for the thirsty. Such customers as fall to the quieter tap of the ‘Lion’ are served by the landlady, an active, bustling body with some little contempt for the slow, niggling work which her husband puts into the old rubbish that she would consign to the flames. Not but what she admits that the money that the old things fetch is a welcome addition to the family purse.

The old man is not contentious by nature, but he enjoys a moment of quiet triumph. ‘She took on about an old chair I brought home the other night,’ he tells you, after glancing round to see whether the good lady is within hearing. ‘I gave five shillings for it. Well, it didn’t look up to much, certainly; but I tell you what, sir, it was a genuine Cromwellian chair, and I never saw another of the same pattern.’ Then, with a twinkle in his eye of self-conscious justification, he adds that two days later a passer-by looked in, saw the chair, and promptly gave him three guineas for it, and sent it across the Atlantic.

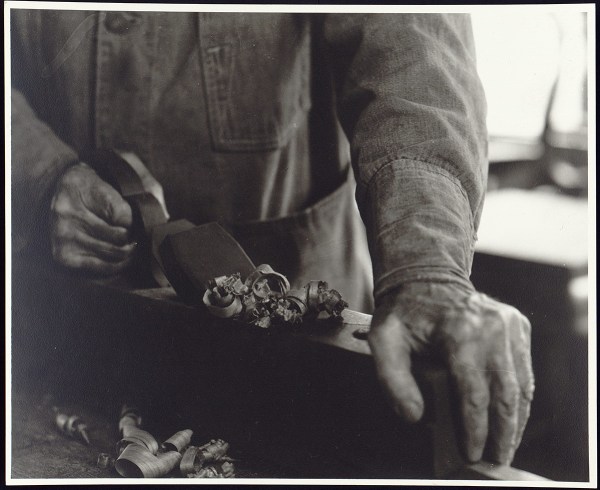

At the back of the inn the old furniture restorer has his workshop, and in a loft over the stable he keeps a miscellaneous store of old chairs, tables, and chests in a shocking state of dilapidation. To the outsider, at any rate, they look shabby enough; but I do not think the old man ever sees them as they are. Like the poet, he ‘looks before and after.’ He always seems to have before him a vision of what they have been and what they may be again.

‘There is a beautiful old table,’ he says to you; ‘genuine Queen Anne.’ Then he rubs his hand caressingly over a dusty table with a cracked top and but three worm-eaten legs. His enthusiasm is hardly catching at the moment; but see the table again in a week or two, and you will admit it looks for all the world as if it had been carefully preserved in the homes of a series of maiden ladies since the day it was made. No vulgar shine or French polish about it, but the rich, sober glow of mellow and self-respecting mahogany. The crack has magically disappeared, and you would need a microscope to find which was the added leg.

The old man is a great stickler for style. Anachronisms pain him as false quantities the classical scholar. His quick eye notes at once an error in date of the locks and handles of an old piece of furniture. ‘You must let me take them off, sir,’ he will say. ‘You can’t have them Chippendale handles on that Jacobean cabinet.’

In old cigar-boxes at home he carefully treasures all odds and ends of ‘furniture,’ as such brass-work is called, and can generally lay his hand on a lock or hinge that is just right; but sometimes he has to fall back on the people who make them for the trade, though he groans over their prices.

When the brass-work of an old piece of furniture is not missing, but only broken, it is a pleasure to see him cutting and filing out pieces to make the old work perfect instead of pulling it off and replacing it by anything, however inappropriate, that comes to hand, as so many of the dealers do. The inaccuracies of the dealers vex him terribly. ‘Those fellows are so ignorant,’ he will say. ‘They ‘ll take a Chippendale table and restore it with Sheraton legs.’

The dealers, on the other hand, have a very great respect for the old man, though they grumble at the amount he charges for his work and the time he takes over it. But they admit that he does turn out good work; and if they have any specially fine piece that wants restoring they come to him. Ordinary jobs they do themselves, and with a touch or two of the plane and a good deal of sand-paper and French polish can dress up the old things to suit their customers; but when they get hold of something that will fetch a good price they like his help and judgment.

Where he gets his old things from nobody knows. He seldom attends auction sales. It is not worth his while, he says; there are too many dealers about. Some old things come from the cottages round about. Probably conversation in the bar of an evening puts him on the scent of many an old chair and table. He will not admit that it is a pity that all the picturesque old furniture should be taken from the cottages to satisfy the demands of fashion.

He will tell you that last winter he got three beautiful ball-and-claw Hepplewhite chairs from a cottage in the village. There had been nine of them, and six had been broken up for firewood before he saw them. He gave the owner half-a-dozen new Windsor chairs for the remaining three, and sold them for three guineas each to a collector. He admits that now and then he has made a good bargain. One of his triumphs was a bureau that he picked up for fifty shillings and sold for twenty-live pounds. ‘But there was a lot of work to be done to that,’ he adds reflectively.

If you ask the old furniture restorer how he learnt his trade, he will tell you that he never served any apprenticeship. In fact, when a young man he was a carpenter in the navy. He ascribes his success entirely to his love for the old stuff.

There are few things he prides himself on more than his knowledge of different woods. ‘You don’t know what that is,’ he will say, showing you a square inch of inlay round the edge of a drawer. ‘Apple; that’s what that is, sir.’ It is not often that apple is wanted; but he has by him a worm-eaten old piece of apple timber that will come in for that particular bit of furniture.

One of his great difficulties is getting old wood for his work. In restoring old furniture, especially where there is much inlaying, he requires all kinds of wood; and from his point of view—and here he differs from many others of his trade—it is essential that the wood shall be really old; preferably as old as the piece in which it is to be used. He buys up anything in the way of old timber that he comes across.

If a beam is taken out of an old farmhouse chimney to make way for a modern grate he will bid for it. He made a great haul of old oak recently from the belfry of a neighbouring church where the bells were being rehung. In fact, so good a stock of old oak has he got that he is a little sore about the change which fashion has taken from oak to mahogany. The only wood he is spiteful about is a species of teak, which he declares is full of sand and blunts his chisel at each cut.

Besides what he earns by selling or restoring old furniture, he has a subsidiary source of income of rather a curious character. In a neighbouring town there is established a great chairmaking industry. The factories are well equipped with machinery, and turn out thousands of chairs a week for the furniture-shops all over the world.

The owners of these factories are always craving for new ideas, and are willing to pay for them; and when the old man gets hold of an old chair of unusual design he takes it over to the factories, and they give him ten or fifteen shillings for the loan of it for a couple of days to copy. For an exceptionally fine example he has got as much as twenty-five shillings for two days’ loan. ‘But you know, sir,’ he says, ‘ the old chairs were not made by chairmakers at all. It was cabinetmakers’ work in the time of Chippendale and Sheraton, and that makes all the difference.’

Altogether, the old furniture restorer embodies a good many of the characteristics of an ideal craftsman. Working in the country among his roses and hollyhocks, his individuality quite unhampered by the limitations of machinery, he shapes and carves the best obtainable material undeterred by the bogy of cheapness. Seen at his bench, surrounded by quaint home-made tools to fit the intricacies of his work, and by bottles of cunning stains for which he alone knows the recipe, he looks like one of the old workers whose individuality is so deeply imprinted on their creations that no one but a like craftsman can restore them to any satisfactory effect.

Chamber’s Journal – June 20, 1903

—Jeff Burks